99. The Planets at Giza

- M Campbell

- 2 days ago

- 39 min read

Updated: 12 hours ago

At first glance, the idea that the planets are encoded at Giza might seem improbable. Yet, when the Great Pyramid complex is treated as a single, coherent design, planned, scaled, and executed according to a unified mathematical logic, something otherworldly begins to emerge. This article proceeds from a simple premise: that at Giza, number, geometry and astronomy are key. If we allow the inch to function not merely as a unit of length but as a unit of time, be it a year, or a day, the architecture begins to behave like a dynamic model. Measures in space become periods of time, but there is barely an instance of a particular cycle being laid out in stone by itself, in isolation from some other cycle. Dimensions translate into combinations of celestial motions.

Within this framework, the inch becomes the key, but not the only one. The metre and the Saxon foot appear repeatedly as coherent companions, not competitors, each capable of expressing the same underlying relationships through different numerical grammars. The Great Pyramid's height, base, perimeter, slopes, and internal measures begin to speak in the language of planetary periods, as do the other two main pyramids at Giza, and the geometry formed bytheir relative positions. Lunar, solar, and planetary cycles coexist without contradiction, nested within one another. If we take the builders seriously as mathematicians of time, the Giza Plateau, approached as a single design and a single problem, reveals itself as something like a beautiful game, a rigorous, playful, and exacting exercise in translating the complexities of the universe into number, proportion, and stone. The sun and moon are very important in the Giza design, but so are the other five 'planets' of the traditional seven. This article focuses on these, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn, and how their cycles are interwoven into the algorithmic fabric of the Giza pyramids.

1. The Great Giza Rectangle (GGR) Length: Seven Planets Set in Motion

If the Giza Plateau is read as a single design, then the Great Giza Rectangle (GGR) length must be treated as foundational. This rectangle is formed by the outer corners of the Great Pyramid, to the north-east, and the third pyramid, to the south-west. Everything else unfolds from it. It's the first move in a larger mathematical construction, an initiating value from which several algorithms proceed. In addition, there is a cosmological generative aspect to this distance, that we can find echoes of in ancient Greece.

In the Timaeus, Plato describes the act of creation as the ordering of motion. The Demiurge sets eight circles into movement: seven moving in one direction, and one in the opposite. These circles correspond to the seven “planets” of antiquity (Sun, Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn) while the eighth, reversing the others, governs the motion of the fixed stars. Read astronomically, this reversal is difficult to interpret as anything other than precession. Plato is articulating a cosmology in which time itself is generated by planetary motion, and in which number and motion are inseparable.

“Next, He split all this that He had put together into two parts lengthwise; and then He laid the twain one against the other, the middle of one to the middle of the other, like a great cross; [36c] and bent either of them into a circle, and join them, each to itself and also to the other, at a point opposite to where they had first been laid together. And He compassed them about with the motion that revolves in the same spot continually, and He made the one circle outer and the other inner. And the outer motion He ordained to be the Motion of the Same, and the inner motion the Motion of the Other. And He made the Motion of the Same to be toward the right along the side, and the Motion of the Other to be toward the left along the diagonal; and He gave the sovranty. [36d] to the Revolution of the Same and of the Uniform. For this alone He suffered to remain uncloven, whereas He split the inner Revolution in six places into seven unequal circles, according to each of the intervals of the double and triple intervals, three double and three triple. These two circles then He appointed to go in contrary directions; and of the seven circles into which He split the inner circle, He appointed three to revolve at an equal speed, the other four to go at speeds equal neither with each other nor with the speed of the aforesaid three, yet moving at speeds the ratios of which one to another are those of natural integers.”(1)

Giza appears to operate within precisely this conceptual world. As F. M. Cornford observed, Plato gives an unusually detailed and technical account of the motions of the heavens in the Timaeus, using number and proportion as the language of creation, a level of explicit mathematical articulation that is largely absent from the surviving Egyptian creation myths, which tend to express cosmology through genealogy, symbol, and divine action rather than formal calculation.

"The conclusion is that the Laws (certainly) and the Epinomis (quite possibly and, I should say, probably) are perfectly consistent with the theory of the Timaeus , which ascribes a compound motion to the seven planets. The conception is fundamental in the system of Eudoxus, who was working at the Academy before the Timaeus was written and who died before Plato. It is equally fundamental in Aristotle's adaptation of Eudoxus’ system of spheres. The system must have been known to Plato, and the probability is that he incorporated in the Timaeus as much of it as he could accept, consistently with his belief that the proper motion of each planet keeps to a circular track. It should not be forgotten that the Timaeus is a myth of creation, not a treatise on astronomy. The surprising thing is that Plato should have found room for so many details in his broad picture of rational design in the cosmos, not that he should have simplified by omitting subtleties which would contribute nothing to his main purpose and which might be superseded at any time, as indeed they were very soon afterwards." (2)

The order that has been imposed on the cosmos by the Demiurge is through number, and geometry. It is this order that can provide and interpretation of the Giza design. The GGR length functions as a planetary register. It encodes the seven planetary cycles, including Earth and the Moon, numerically. This is why its length is foundational: it is the source value from which the site’s time-based geometry is derived. The interpretive key is deceptively simple: one inch is treated as one year (and, elsewhere, as one day). Once this principle is applied consistently, the GGR becomes a timeline, a sort of compressed map of celestial motion. Importantly, this does not exclude other units. Metres, cubits and Saxon feet recur throughout the site, but they do so coherently, translating the same relationships through different numerical systems. The inch, however, is the most explicit carrier of time. Here are the most accurate sidereal periods (and the Earth sidereal year definition I’m using).

Body (sidereal period) | Period (in Earth sidereal years) |

Mercury | 0.24084 |

Venus | 0.61519 |

Mars | 1.88082 |

Jupiter | 11.86178 |

Saturn | 29.44781 |

Moon | 0.07480 |

The length of the rectangle, approximately 35 713.2 inches, appears to encode a planetary product. If we multiply the sidereal orbital periods of Mercury (0.24084 years), Venus (0.61519 years), Earth (1 year), Mars (1.88082 years), Jupiter (11.86178 years), Saturn (29.44781 years), and the Moon (0.07480 years), and then include the Metonic cycle (19 years) and a precessional factor, estimated here at 25815 years, before dividing the result by 100, we obtain a value of 35 715.10 inches, which is extremely close to the measured length of the rectangle reported by Flinders Petrie.

In earlier notes I used Mercury ≈ 0.24 Earth-years as a convenient shorthand together with a traditional value for precession, 25 920 years. This gave an almost perfect match to Petrie's measurement. Here, however, I use modern sidereal periods consistently for all bodies, to five decimal points, converting them to Earth-years using an Earth sidereal year of 365.25636 days. With this consistent modern dataset, adopting a commonly cited modern precessional period yields a small residual mismatch at the inch level. If, instead, precession is treated not as a fixed input but as a quantity encoded by the design, solving the equation against the measured GGR length implies a precessional period of approximately 25 815 years, within about 0.2% of modern astronomical estimates.

0.24084 × 0.61519 × 1.88082 × 11.86178 × 29.44781 × 0.0748 × 25 815×19 / 100 = 35 712.09

The rectangle’s length appears to have been designed to reflect astronomical cycles expressed in Earth years, reinforcing the idea that time, rather than distance alone, was the true quantity being measured. Within this framework, a striking connection emerges with the historically important number 28, a perfect number and one long associated with the Moon.

Using a canonical planetary product (Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and the sidereal Moon), together with the Metonic cycle and a traditional precessional constant, the expression

100 000 000 / (0.24084 × 0.61519 × 1.88082 × 11.86178 × 29.44781 × 0.0748 × 25 815×19) ≈ 28.0017

lands extremely close to 28. Remarkably, the measured length of the rectangle is itself within a few inches of 1 000 000 / 28 inches, suggesting that this number operates as a structural attractor within the design.

The number 28 appears elsewhere at Giza. Most famously, the height of the Great Pyramid of Giza is 280 Egyptian royal cubits, a measure which converts to approximately 20.63 inches (or 0.524 m) per cubit. Whether approached through architecture or arithmetic, the same lunar-associated number repeatedly asserts itself.

Alongside this, there are further numerical convergences that give pause for reflection. If the sidereal cycles of the seven traditional planets are multiplied together, again expressed in Earth years, the result is approximately 7.281. When multiplied by 50, this yields 364, which is exactly 13 × 28, two numbers of great importance in ancient calendrical systems.

The 364-day year is a schematic or computational year, composed entirely of whole weeks. Unlike the tropical or sidereal solar year, it is designed to harmonise seven-day planetary weeks with 28-day lunar revolutions. Such a year appears in several ancient traditions as a counting framework for longer cycles. It is therefore striking that the sidereal planetary periods, when multiplied together and scaled by 50, give 13 × 28, while those same periods, when combined with the Metonic cycle and precession and divided by 100, yield a value close to 1 000 000 / 28. Different operations, the same numerical centre of gravity.

One is tempted to note, cautiously, how often 13 and 28 recur together in cosmological traditions far removed from Egypt. In Mesoamerican astronomy, for example, time was structured around cycles of 13 and 20, and the turtle, often depicted with thirteen divisions on its shell, served as a cosmological support or bearer of the world. In other mythic settings, a great turtle or similar creature underlies the ordered heavens. Whether coincidence, shared arithmetic intuition, or something deeper, it is at least suggestive that precessional time, the slow turning of the heavens, so often seems to “rest” on a framework built from these same numbers.

If, however, we omit the Metonic factor of 19, the same expression becomes:

100 000 000 / (0.24084 × 0.61519 × 1.88082 × 11.86178 × 29.44781 × 0.0748 × 25 815) ≈ 532

The appearance of 532 is especially significant, as 28 × 19 = 532, linking the lunar-associated number 28 directly with the Metonic cycle.

The number 532 years is well known in the later Christian calendrical tradition as the Great Paschal Cycle. It represents the period after which Easter Sunday and other movable feasts repeat on the same calendar dates and the same days of the week in the Julian calendar. This cycle arises from the combination of two independent rhythms: the 28-year solar cycle and the 19-year Metonic lunar cycle.

The 28-year solar cycle is the time required for the days of the week to realign with calendar dates in a 365-day calendar with leap years every four years. Each year, a given date advances by one weekday; every leap year introduces an additional shift. After 28 years, the pattern of weekdays and dates repeats exactly. This cycle depends fundamentally on a seven-day week, without which such periodicity would not occur.

When the 28-year solar cycle is combined with the 19-year Metonic cycle, the result is a 532-year period in which both the lunar phases and the weekdays realign. After this interval, the entire sequence of Easter dates repeats identically. The Gregorian reform of 1582 modified the leap-year system to correct the accumulated drift of the equinox in the Julian calendar, meaning that the strict 532-year cycle applies only to the Julian system. Nonetheless, the underlying idea, reconciling solar and lunar cycles over long spans of time, is far older.

While there is no evidence that the 532-year Easter cycle was directly inherited from ancient Egyptian or Babylonian astronomy, the principle it embodies is entirely traditional. Ancient cultures repeatedly sought to harmonise lunar months, solar years, and planetary periods within longer computational frameworks. The seven-day week itself is extremely ancient, attested in Mesopotamia and India long before the Christian era, and it is this seven-day rhythm that makes a cycle such as 532 years possible at all.

Seen in this light, it is striking that the same sidereal planetary cycles which generate 28 when combined with the Metonic cycle and precession also generate 532 when the Metonic factor is removed. Different paths through the arithmetic return related numbers, suggesting not coincidence but a system structured around a small family of deeply interlocking cycles.

As the GGR length is expressed in inches and read as years, it resolves into a structured sequence of the seven planetary sidereal cycles, including the sidereal Moon, we can say it functions as the first step in a generative process. From this length flow the dimensions of other parts of the Giza complex. In modern terms, we might say the GGR supplies the initial conditions of the system. In ancient terms, it is the moment when the circles are set in motion. The plateau becomes a mathematical enactment of a creation story in which the universe is ordered through number, and time itself is the true substance being measured.

The results discussed above should not be understood in isolation. The Great Giza Rectangle (GGR) functions as more than a single measurement: it behaves as a generative value, from which other key dimensions across the plateau can be derived.

Once the GGR length is established, whether interpreted through the “seven planets × precession” construction, or through its proximity to 1 000 000 / 28 inches, it becomes a starting point for a series of transformations. Through well-defined operations involving π, √3, the lunar month, and calendrical cycles such as the Metonic and Saros periods, the base lengths and heights of the three main pyramids can be produced from the same numerical source. In this sense, the Great Pyramid does not merely encode astronomical knowledge; it anchors an algorithm. The GGR supplies the initial condition, and the rest of the plateau unfolds from it through a limited repertoire of operations. This is why planetary, lunar, and precessional numbers recur across multiple structures in different guises: they are not being independently “inserted” each time, but regenerated from the same numerical seed.

Such behaviour is characteristic not of ad hoc numerology, but of a system designed to be internally consistent, memorable, and transmissible.

The repeated emergence of 28 across these constructions deserves some reflection. At a minimum, 28 is inseparable from the Moon: it is the nearest whole number to the synodic month in days, and it structures lunar quarters (4 × 7) with remarkable elegance. It is also a perfect number, equal to the sum of its proper divisors (1 + 2 + 4 + 7 + 14), a property that gave it special status in later mathematical traditions.

At Giza, 28 appears not only in calendrical reconstructions, but in architecture itself: most famously in the 280 royal cubits traditionally associated with the height of the Great Pyramid. It also re-emerges when large cosmological numbers are scaled down, for example in expressions clustering around 1 000 000 / 28, or when planetary products resolve to 13 × 28 and 19 × 28 = 532, numbers that underpin long-range calendrical reconciliation.

Beyond Egypt, the pairing of 28 with 13 and 20 recurs in other cosmological traditions concerned with timekeeping and renewal. While no direct line of transmission need be assumed, the convergence is suggestive: 28 repeatedly functions as a mediating number, capable of harmonising weeks, lunar months, solar years, and longer cycles within a single arithmetic framework.

In this light, 28 does not stand for one thing alone. It acts instead as a numerical hinge, a point where different measures of time can meet without friction.

2. Mercury: The Fastest Cycle

Mercury is the sprinter of the planets. Its sidereal period, the time it takes to complete one circuit of the Sun relative to the fixed stars, is 87.9691 days, or about 88 days.

Using the tropical year of 365.242199 days and the lunar year of 354.36708 days, the side length of the Great Pyramid can be written in inches as: 87.9691 × 365.242199 / 354.36708 × 100 = 9066.877 (or using 88, it's about 9070.8 inches), close to Petrie’s measured side length (mean side of 9068.8 inches). This is also where the traditional “440 cubits” becomes interesting. Read plainly, it is a conventional architectural value. But it is also 5 × 88, or five Mercury years of 88 days.

A further Mercury connection appears in the dimensions of the third pyramid. If Mercury’s sidereal orbital period is expressed in Earth-years (0.24084), then dividing 1000 by this value yields:

1000 / 0.24084 = 4152.13

This is within just over an inch of Flinders Petrie’s mean measured side length for the Third Pyramid (G3). Once again, time appears to be translated directly into architecture, with a planetary period acting as the generative quantity.

This expression can also be understood in calendrical terms. The same value arises when a yuga of 4 320 000 sidereal years is normalised by a Metonic cycle and by 25 lunar years (300 synodic months), and then scaled by 100. In this way, Mercury’s cycle functions as a mediator between very long astronomical periods and architectural dimensions measured on the ground.

Given Mercury’s traditional association with reckoning, measure, and mediation between scales, its appearance at Giza in this role is particularly fitting, not symbolically, but operationally.

The vertical dimension of the Third Pyramid reinforces this interpretation. Dividing the base side by the golden ratio (φ ≈ 1.61803) gives a height of approximately 2566 inches. This value can again be expressed astronomically:

4 320 000 × 365.25636 / (25 × 354.36708 × 19 × 365.25636) × 100 = 2566.48

Here the sidereal year cancels, leaving a structure defined by lunar years, the Metonic cycle, and a decimal scaling, consistent with the way time has been converted into length elsewhere at Giza.

Remarkably, this height can then be returned to a round canonical value through a further geometric–lunar transformation:

2566.48 × 2 √3 × 254² × ϕ / (29.53059 × 10 000 π) ≈1000

Dividing this result once more by Mercury’s sidereal period expressed in Earth-years closes the loop, returning us to the original planetary cycle. Mercury thus appears at Giza not as an isolated curiosity, but as part of a reversible system in which planetary motion, lunar cycles, geometry, and architectural scale are continuously transformed into one another.

What is striking about Mercury’s appearance at the Third Pyramid is not only the numerical fit, but its position within the broader system. The Third Pyramid sits at the terminus of the main scaling sequence that begins in the King’s Chamber. Mars’s sidereal period enters the system at chamber scale; geometry and lunar factors expand it to the Great Pyramid; Metonic scaling extends it again to the Great Giza Rectangle. Mercury then appears precisely where this expansion reverses.

By expressing the side of the Third Pyramid as 1000 / 0.24084 inches, the system converts a large architectural dimension back into a single planetary period. In this sense, Mercury acts as a closing operator. The same planetary logic that unfolds outward from Mars (as we shall see in the King's Chamber) returns inward through Mercury, producing a closed and reversible chain. Mercury does not introduce a new idea into the system; it resolves an existing one. Where Mars mediates between sidereal and synodic time, Mercury mediates between scale and unit. The Third Pyramid functions as a point of compression, where the accumulated products of planetary, lunar, and precessional time collapse back into a single, intelligible cycle.

3. Venus

Venus is represented by the width of the GGR, which represents 80 years, so 10 cycles of 8 years. The width of the Great Giza Rectangle is 29 227.2 inches and this is very close to 80 x 365.25 = 29 220 days. Eighty solar years correspond to ten Venus cycles of eight years, and 99 lunations. Eight solar years are also 2 Sothic cycles of 4 Julian years days (365.25 days), which also corresponds to the period between Olympic games.

A connection to a Venus day can also be found by combining the sides of the Great and third pyramids. If the values for these measures are given in metres, then the resulting rectangle has an area of 24 300 square metres. A Venus day lasts for 243 earth days. Using Petrie’s values:

Great Pyramid side ≈ 230.3475 m

Third Pyramid side ≈ 105.4938 m

Lastly, for Venus, if the number of sides of the Great Pyramid is taken to be eight, instead of four, and indeed this is the case if we consider the very slight division of each side into two parts, visile only under certain light conditions, then perhaps this can also be connected, symbolically at least, to Venus.

4. Saturn

Skipping ahead to Saturn, as, though I expected Saturn, being the god of time, to be the most represented planet at Giza, I found that in fact Mars was the most important, so Mars comes last in this article.

9 072 inches = 24 × 378

or 9 072 inches = 2 × 378 feet (if 1 foot = 12 inches)

where 378 is treated as a Saturn-related count. The important point is not to insist on one reading, but to show that the Great Pyramid side sits at a junction where several cycle-count languages can meet.

The same logic applies to Saturn, whose sidereal orbital period is approximately 10,755.7 days. Using the yuga but with a year of 366 days, and scaling now by 1,000 instead of 10,000, the result appears in metres:

4 320 000 x 366 / (10 775.7 x 1000) = 146.73

146.73 metres are 5776.8 inches, which is to within an inch of Petrie’s value.

We can also interpret the side of Great Pyramid in inches as 24 x 378 = 9072, with 378 being the number of days in Saturn's cycle. Or we could read the side of the Great Pyramid as 2 x 378 feet.

Another planetary resonance appears at a more local scale within the fabric of the Great Pyramid itself. Petrie noted that the entrance passage of the pyramid exited the original outer casing at the nineteenth course of masonry, and that this was consistent with a general rule across several pyramids. The bottom of this course lies 668.2 inches above ground level, the top at 706 inches, giving a course height of 37.8 inches. This value is not inferred or reconstructed, but measured directly from surviving evidence.

The number 37.8 is striking when viewed astronomically, as it corresponds, by a factor of ten, to the synodic period of Saturn, which is approximately 378 days. Saturn, the outermost planet visible to the naked eye, was widely associated in ancient cosmologies with time, limitation, and thresholds. The appearance of its number at the precise architectural point where the pyramid transitions from exterior to interior is therefore suggestive. It places Saturn not at the cosmic scale of the pyramid as a whole, but at the gate, marking passage from the visible world into the hidden interior.

When considered alongside the lunar and solar relationships already noted in the pyramid’s height and base, the Saturn correspondence at the entrance threshold strengthens the impression that planetary cycles were embedded at multiple scales. The Moon governs the pyramid’s height through the sidereal month; the Sun appears through the year; the Earth through circumference and measure; and Saturn, lord of boundaries and long cycles, appears at the architectural point of transition. Whether intentional or emergent, this layered structure reflects a worldview in which planetary order, time, and sacred architecture were not separate domains, but different expressions of the same cosmic harmony.

The original entrance of the Great Pyramid marks the transition from the exterior to the interior of the monument and corresponds numerically to the synodic period of Saturn (≈378 days), a planet traditionally associated with boundaries, time, and limits. It is also notable that the midpoint of the nineteenth casing course lies at approximately 687 inches above the base, a number corresponding to the sidereal period of Mars in days. While this midpoint has no independent architectural significance, its appearance alongside the Saturnian course height is at least consistent with the broader planetary framework discussed here, in which thresholds and passages appear to occupy zones resonant with planetary cycles.

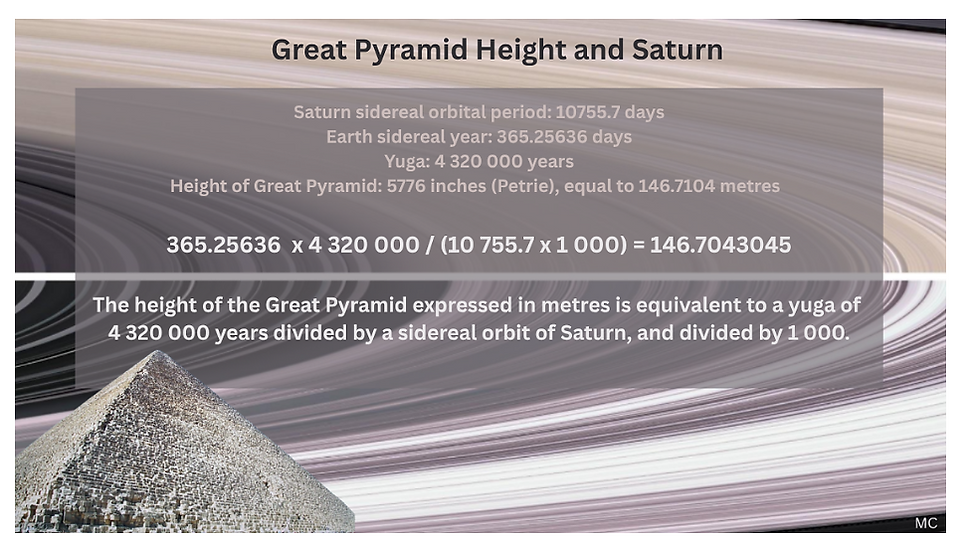

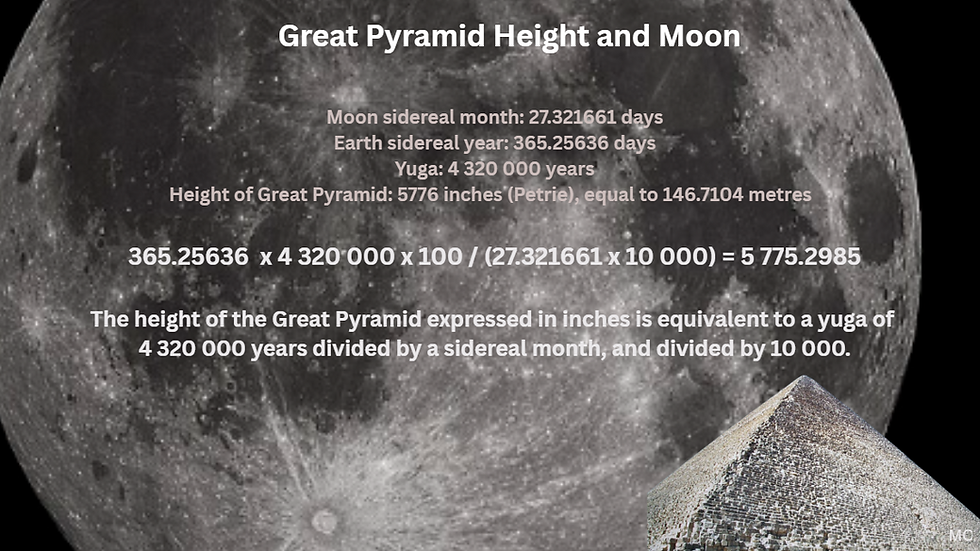

The same logic applies to Saturn, whose sidereal period is approximately 10,755.7 days. When the yuga is divided by Saturn’s orbit and scaled by 1,000, the result appears not in inches but in metres: 4 320 000 x 365.25636 / (10 755.7 x 1000) = 146.70 metres

This is essentially identical to the Great Pyramid’s original height of 146.7 metres.

But what is a metre? It can be several things, but here we can think of it as the inverse of the number of sidereal months in a Metonic cycle (254), multiplied by 10 000, expressed in days and inches, as a metre is 10 000 / 254 inches. Or we can think of it as the link between the tropical year and the synodic month, or between the number of years (19) and the number of synodic months (235) in a Metonic cycle, filtered through the geometry of the circle.

19 π x 1000 / 254 = 235.001

So seeing the height of the Great Pyramid as an expression of Saturn’s sidereal period therefore also brings the sun and moon into play. To go back to inches, the height can be interpreted as the number of sidereal periods of Saturn in a yuga of 4 320 000 sidereal years of 365.25636 days, divided by the number of sidereal months in a Metonic cycle (254).

4 320 000 x 365.25636 x 10 / (254 x 10 755) = 5775.76

Dane Quirk has also found that the height can be interpreted as 364 / 378.03 x 6000 = 5777.32 inches.

What this reveals is not a collection of coincidences, but a hierarchical design principle: the same structure can encode different planetary cycles, using different units (for example inches and metres), perhaps scaled up or down by powers of ten. The Great Pyramid thus appears to function as a cosmic index, a fixed reference point from which the Moon, Jupiter, and Saturn can all be read as harmonics of a single, overarching time cycle.

5. Mars as the Dimensional Generator of the King’s Chamber

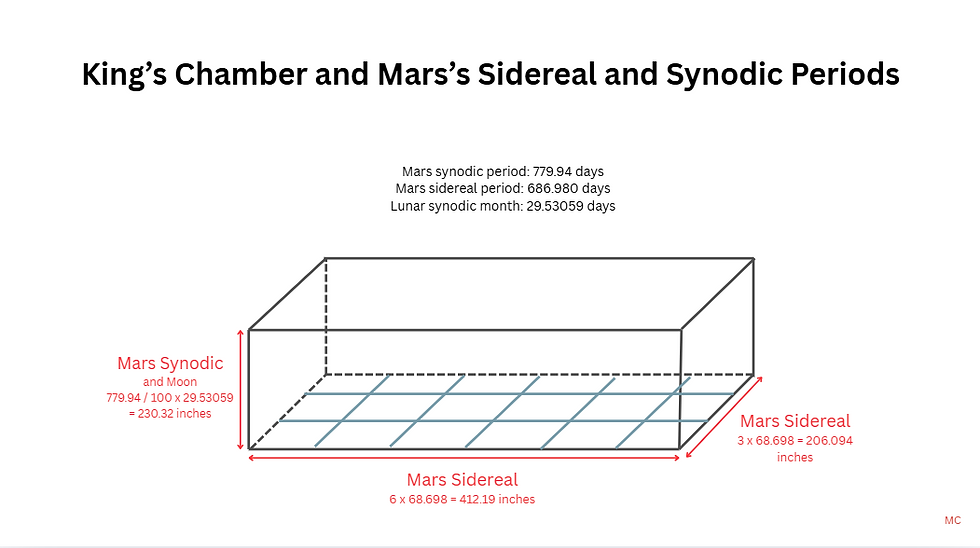

Among the seven traditional planets, Mars emerges as the most structurally active within the Great Pyramid. Nowhere is this clearer than in the dimensions of the King’s Chamber, whose proportions correspond closely to Mars’s orbital cycles when those cycles are expressed in days and translated directly into inches through simple decimal scaling.

Mars has two principal orbital periods of interest: its sidereal period, measuring its motion relative to the stars, and its synodic period, measuring its cycle of recurrence relative to the Sun and Earth. Both appear to be present in the King’s Chamber, each governing a different spatial dimension.

The sidereal orbital period of Mars is 686.980 days (often rounded to 687). If this value is reduced by a factor of ten, two simple expressions emerge:

686.980 × 6 / 10 = 412.188 inches

686.980 × 3 / 10 = 206.094 inches

These values correspond strikingly to the chamber’s length and width. Flinders Petrie gives the mean length of the King’s Chamber as 412.4 inches and the mean width as 206.1 inches, placing the Mars-derived values within a few tenths of an inch of the measured dimensions. At this scale, the agreement is well within the tolerance of both ancient construction and modern survey.

This relationship can be visualised in another way. If the chamber floor is divided into 18 equal squares, arranged as a 3 × 6 grid, each square has sides of approximately 68.7 inches, a tenth of Mars’s sidereal period in days. The chamber thus resolves into a simple modular grid derived directly from Mars, reinforcing the idea that the planet’s cycle functions here as a governing unit of scale rather than as an abstract symbolic reference.

Mars’s influence is not confined to the horizontal plane. The height of the King’s Chamber appears instead to reflect Mars’s synodic period, which measures 779.94 days. Petrie gives the chamber height as 230.09 ± 0.15 inches. If Mars’s synodic period is divided by 100 and multiplied by the length of the synodic lunar month in days (29.53059), the result is:

779.94 / 100 × 29.53059 = 230.32088 inches

Once again, the agreement with the measured value is close, differing by only a few tenths of an inch. The implication is clear: the base dimensions of the chamber correspond to Mars’s sidereal cycle, while the vertical dimension corresponds to Mars’s synodic cycle.

Taken together, these relationships suggest that the King’s Chamber functions as a Mars-scaled module, in which time is translated into space through direct numerical equivalence. No complex geometry is required at this stage, only decimal scaling and consistent unit use. If Petrie’s measurements do indeed reflect the intended design, the precision involved is extraordinary.

At this foundational level, before geometry, proportion, or metrology are introduced, Mars already governs the chamber’s form. The chamber does not merely accommodate Mars symbolically; it embodies Mars numerically, with its dimensions expressing both the planet’s stellar cycle and its solar rhythm in stone.

Once the dimensions of the King’s Chamber are established through Mars’s orbital cycles, its geometry begins to speak for itself. The chamber’s plan is a 1:2 rectangle, often described as a double square.

In a double square, the diagonal of the rectangle is equal to the width multiplied by √5. This relationship follows directly from the Pythagorean theorem and requires no prior knowledge of irrational numbers as abstract entities. It is simply what the geometry does. Once a rectangle of this form is drawn, √5 is present. Using Flinders Petrie’s mean measurement for the chamber width (206.1 inches), the diagonal of the floor is therefore:

206.1 × √5 ≈ 460.85 inches

Half of this diagonal is approximately 230.43 inches, a value strikingly close to Petrie’s measured height of the King’s Chamber (230.09 ± 0.15 inches). Petrie himself noted that the diagonal of the chamber floor bears a simple relationship to its height, noting: "Diagonal of floor of King's Chamber is double its height."

√5 arises as a geometric consequence of a simple rectangular form once that form has been fixed by a numerical generator, the Mars-scaled dimensions already described. The double square is a generative figure: from it arise diagonals, mediating proportions, and latent relationships that can later be expressed in different ways. Geometry here is not decorative or symbolic; it is operative. The King’s Chamber does not display geometry as an aesthetic flourish, but uses it as a means of translating numerical relationships into spatial form.

Seen in this light, the geometry of the chamber follows directly from its role as a Mars-scaled module. Mars determines the rectangle; the rectangle determines √5, which in turn governs the relationship between plan and elevation. The chamber thus becomes a space in which number gives rise to geometry, rather than geometry being imposed independently of number.

From √5, the golden ratio φ follows just as naturally. The relation

φ = (1 +√5)/ 2 is a practical consequence of a double square also. There is no reason to suppose that such relationships were unknown to the architects of the Great Pyramid. On the contrary, the consistent and disciplined way in which proportional mediation appears at Giza strongly suggests a working familiarity with irrational ratios, even if they were expressed geometrically rather than algebraically.

The chamber is not laid out according to a golden-ratio rectangle, but as a double square.

Using the measured width of the chamber, approximately 206.1 inches, one can derive a φ-scaled length directly from the diagonal geometry: (206.1 × 5) + 206.1 / 2 ≈ 333.5

This value recurs in several internal relationships. The sum of the chamber’s height and half its width lies very close to this φ-derived length, meaning that a vertical line of approximately 333 inches drawn along the longer wall resolves the space into a precise internal balance: the remaining segment corresponds closely to half the chamber’s width.

φ also asserts itself at the scale of the chamber’s perimeter. The semi-perimeter lies close to 1 000 / φ, and the full perimeter to 2 000 / φ, within the tolerances of both ancient construction and modern survey. Here φ functions as a scaling ratio, translating internal dimensions into a coherent boundary measure.

These φ-based relationships do not operate in isolation. They sit alongside solar–lunar ratios already discussed, such as the relationship between the tropical year and the synodic month, which produces values clustering in the same numerical range when scaled appropriately. In this way, φ participates in a broader system of mediation, linking geometry with calendrical time.

It would therefore be misleading to treat φ as a symbolic add-on or as an accidental curiosity. Nor does its presence require us to imagine a culture unaware of irrational numbers. A far simpler explanation is that the builders worked confidently with figures such as the square, the double square, and the vesica, whose diagonals and proportions naturally yield √5, φ, and related constants.

In the King’s Chamber, φ acts as a mediator, linking dimensions, allowing relationships between Mars-scaled measures, solar–lunar ratios, and architectural boundaries to cohere.

Seen in this light, φ at Giza is the natural outcome of a geometric language sophisticated enough to translate planetary time into architectural form.

The role of Mars within the King’s Chamber becomes fully intelligible when the Sun and the Moon are brought into the picture. At this stage, it is no longer sufficient to note that Mars’s sidereal and synodic periods both appear; what matters is how they appear, and what they are mediating.

The chamber’s horizontal dimensions, width and length, are governed by Mars’s sidereal period, the planet’s motion relative to the stars. As shown earlier, simple decimal reductions of the sidereal cycle yield the chamber’s plan with remarkable precision. By contrast, the vertical dimension, the height of the chamber, is governed by Mars’s synodic period, expressed through the synodic lunar month. In other words, stellar time lies in the plan; solar–lunar time rises vertically.

The synodic cycle is, by definition, a cycle of recurrence governed jointly by the Sun and the Earth, and its expression through the lunar month explicitly brings the Moon into play. The height of the King’s Chamber thus stages the interaction between Mars’s synodic period and the lunar synodic month, while the floor plan remains anchored in stellar reference.

Once this distinction is recognised, further solar–lunar relationships emerge naturally within the chamber’s dimensions.

If we take the Mars-derived module of 68.7 inches (one tenth of Mars’s sidereal period in days), and combine the chamber’s width and length in the proportion already implicit in the plan, we obtain:

68.7 × 3 + 68.7 × 12 = 68.7 × 15 = 1030.5

This value lies extremely close to a fundamental solar–lunar ratio. Using modern values:

365.242199 / 354.36708 × 1000 = 1030.69

Here, 1030 represents the ratio between the tropical solar year and the lunar year, scaled by 1000. The closeness of these values is striking, especially given that they arise from entirely different routes: one from Mars-scaled chamber geometry, the other from astronomical cycles of the Sun and Moon.

The same dialogue appears at the level of the chamber’s perimeter. When the chamber’s dimensions are combined, the perimeter falls close to a solar–lunar ratio scaled by a factor of 100, again linking linear measure to calendrical time. These are not isolated coincidences but repeated expressions of the same mediating logic.

The height of the chamber completes this picture. As shown earlier, the height corresponds closely to:

Mars synodic period / 100 × synodic month

This places the Moon explicitly in the vertical dimension of the space. The King’s Chamber thus becomes a three-dimensional diagram in which sidereal Mars governs the horizontal plane, while synodic Mars, expressed through the Moon, governs the vertical axis. The Sun enters implicitly through the synodic framework itself, since synodic periods are defined by solar alignment.

Mars is uniquely suited to this role. It is the only planet whose sidereal and synodic cycles are both numerically tractable and architecturally expressive at human scale. Faster planets collapse too quickly into short periods; slower planets extend beyond manageable architectural expression. Mars sits between these extremes, capable of linking stellar reference, solar recurrence, and lunar rhythm within a single coherent system.

In the King’s Chamber, this mediation is not symbolic but operational. The space does not merely allude to the Sun and Moon; it reconciles their cycles through Mars. Time is not represented abstractly but resolved into proportion: horizontal and vertical, plan and elevation, star-based and phase-based. The chamber thus stages a quiet but rigorous dialogue between the three great temporal frameworks of the ancient world, stellar, solar, and lunar, using Mars as the connecting term.

This is why Mars is not simply one planet among others at Giza. Within the King’s Chamber, it functions as the pivot through which different kinds of time are brought into alignment, translated into number, and stabilised in stone.

What makes Mars so compelling at Giza is not only that it appears in the King’s Chamber, but that the same small set of operations reappears when we scale outward. The King’s Chamber behaves like a geometric seed: once its Mars-based dimensions are fixed, √5 and φ arise from the double square, √3 enters through vesica-like mediation, and π appears where linear measures are made to coincide with circular ones (especially in metres and perimeters). The result is a family of transformations that repeatedly regenerate key Giza dimensions.

A striking reading (first noted by Jim Wakefield) is that Mars’s sidereal period in days corresponds closely to the Great Pyramid side expressed in Saxon or Sumerian feet of 13.2inches:

686.980 ×13.2 = 9 068.136 inches

This is within about an inch of Flinders Petrie’s mean value for the base side. I remember feeling very impressed and intruigued by his discovery. It was because of his find that I looked for more and more planetary connections at Giza.

Mars's synodic period multiplied by a synodic month also gives the base side in metres. So, using Mars’s synodic period (779.94 days), divided by 100 and multiplied by the synodic month:

779.94 / 100 × 29.53059 = 230.32088

230.32088 as a value in metres is close to Petrie's value. Converted to inches this gives 9067.751 inches, again within about an inch of Petrie’s value. If we round Mars’s synodic period to 780, then the result is closer still, 9 068.449 inches, about half an inch below Petrie's value

Using the relation 1 metre = 10 000 / 254 inches, the same construction can be written:

779.94 × 100 × 29.53059 / 254 = 9 067.75

This is conceptually rich because it pulls 254 into the base side: a Metonic-scale lunar count, now sitting inside a Mars-based derivation of the pyramid’s primary measure.

The base side can also be written as a hybrid of Mars synodic time and the tropical year, mediated by π:

779.94 × 365.242199 / (10π) = 9 067.598

A useful associated value here is: 365.242199 × 10 / 29.53059 × π = 39.3694, which can be read as a solar–lunar ratio scaled into inches, with π acting as the circular mediator.

And because we can express the base as 29.53059 × 100 × 780 / 254 ≈ 9 068.45 inches, we can rearrange and say that a Mars synodic cycle of ~780 days is being compared, in a structured way, to other cycle-count systems through the factor:

254 / (100×29.53059)

Take Petrie’s measured width of the King’s Chamber as a unit (206.1 inches). Because the chamber is a double square: the diagonal introduces √5, and from √5 we obtain φ, and therefore φ-scaled widths. Using the chamber width, the expression:

(206.1×5) + 206.1 is simply the width multiplied by φ.

Now comes the key propagation step:

Width × φ × 3 × 10 ≈ 5 775.99 inches, which is essentially the reconstructed original height of the Great Pyramid in inches. Since the width itself derives from Mars’s sidereal period via simple decimal scaling, the same relation can be written more compactly as:

Mars sidereal × 3 × φ × 3 ≈ Height of the Great Pyramid

This is one of the places where the system becomes unmistakably algorithmic: Mars → chamber module → √5 → φ → √3 → pyramid height.

A further coherence check is that the Great Pyramid height is well approximated by:

10 000 / √3 inches. Rearranging the Mars–φ–√3 relationship gives an expression for Mars’s sidereal period:

10 000 / 9 × φ = 686.70

The modern value is 686.98 days, placing this within hours. Again, the weight of the argument lies less in any single match than in the repeated appearance of the same operators (10 000, √3, φ, simple integers) across scales.

There is a powerful closed-loop identity chain, essentially saying that:

Mars (sidereal) combined with φ, √3 and π yields the Great Pyramid base, and

when the same expression is normalised by the Mars-synodic / lunar-month construction, it returns ~1.

In your compact form: Mars sidereal × 3 × 1.618 × √3 × π/2 ≈ Great Pyramid base

and

Mars sidereal × 3 × 1.618 × √3 × π / 2 × 254 / (100 × 29.53059 × 779.94) ≈ 1.0006

which implies:

Mars sidereal × 3 × 1.618 × √3 × π / 2 × 254 / (100 × 29.53059) ≈ Mars synodic

Numerically:

686.98 × 3 × 1.618003 × √3 × π / 2 × 254 / (100 × 29.53059) = 780.358

This is extremely close to the synodic period scale. Conceptually, it shows the system transforming Mars sidereal into Mars synodic using the same constants that already arise naturally from the chamber geometry (√5 → φ) and vesica-type mediation (√3), with π entering through circular equivalence.

The plateau: Mars numbers outside the pyramid

Mars-related numbers appear not only in the Great Pyramid and its chamber geometry but also in site-scale distances.

Petrie gives the distance between the centres of G1 and G3 as 36 857.7 inches. This distance is close to the Great Pyramid side multiplied by a factor involving 254:

GP side × 254 × 16 / 1000

There is also a clean Mars–Moon construction for the same distance:

779.94 × 29.53059 × 8 / 5 = 36 851.34

This uses only Mars’s synodic period, the synodic month, and the fraction 8/5, and lands within a handful of inches of Petrie’s centre-to-centre measure. It is also close to 78 × 12 metres, within a few inches, strengthening the sense that Mars-lunar time is being projected onto the plateau through simple scalings.

At this point the pattern is hard to ignore. Across chamber, pyramid, and plateau, the same elements recur:

Mars sidereal and Mars synodic as the time-generators

decimal reduction (×3/10, ×6/10, ÷100)

the double square’s unavoidable √5, yielding φ

√3 as a mediator

π where perimeters, metres, or circular equivalences appear

254 as a lunar–Metonic scaling constant that repeatedly locks the transformations

This is why the King’s Chamber can be described as a seed. It is not merely that the chamber “contains” Mars; it is that once Mars fixes the chamber, the chamber’s geometry generates √5 and φ, which then, together with √3 and π, allow Mars-based quantities to propagate outward to the Great Pyramid’s primary measures and then to the layout of the wider plateau. In short, time cycles give rise to number, these numbers as a collection give rise to geometry, and the set of connections generated gives rise to algorithms, and ultimately, to architecture and the site plan, at every scale.

.

.

The role of Mars at Giza becomes clearer when we step back from individual architectural correspondences and look instead at the natural numerical neighbourhood in which Mars’s cycles reside. The sidereal period of Mars (686.980 days) lies at a point where simple arithmetic operations bring it repeatedly into close alignment with lunar, solar, and geometric quantities. These alignments are not exact identities, but they are close enough to encourage stabilisation through geometry.

A striking example is the relationship between Mars’s sidereal and synodic periods. If we take Mars’s sidereal period and combine it with √5, introduced naturally by the diagonal of the double square, we obtain a value close to the synodic period:

686.980 × 3 / 2 × √5 × 10 / 29.53059 ≈ 780.276

This lies very close to Mars’s synodic period of 779.94 days. The implication is not that √5 is being “used” symbolically, but that the geometry of the double square provides a natural bridge between Mars’s two fundamental cycles.

Similar near-resonances link Mars to the Sun and Moon. If we take a Mars-derived module of 68.7 inches (one tenth of Mars’s sidereal period), then:

68.7 × 3 + 68.7 × 12 = 68.7 × 15 = 1030.5

This value lies extremely close to the ratio between the tropical year and the lunar year, scaled by 1000:

365.242199 / 354.36708 × 1000 = 1030.69

Once again, the relationship is not exact, but the proximity is remarkable. It suggests that Mars’s sidereal period naturally mediates between solar and lunar time when expressed through simple integer groupings.

The same mediation appears in another form. Mars’s sidereal period multiplied by the synodic month and scaled appropriately yields the tropical year:

686.980 × 29.53059 × 18 / 1000 ≈ 365.1

Rearranged, this implies:

686.980 × 18 / 1000 ≈ tropical year / synodic month, a ratio that lies close to 20 / φ, further linking Mars to proportions that arise naturally once √5 is present in the geometry.

Taken together, these near-equalities explain why Mars lends itself so readily to architectural expression. From them follow a series of clean dimensional correspondences:

Mars sidereal × 3 / 10 ≈ width of the King’s Chamber

Mars sidereal × 6 / 10 ≈ length of the King’s Chamber

Mars sidereal × 3 × φ × √3 ≈ height of the Great Pyramid

Mars sidereal × 3 / 2 × √5 × 1000 / 254 ≈ side of the Great Pyramid (and, by extension, the height of the King’s Chamber)

10 000 / (9 × φ) ≈ 686.70, within a fraction of a day of Mars’s sidereal period

These relationships are almost uncanny in their closeness, yet they rely only on small integers, simple fractions, and geometric constants that arise naturally from the forms already present. The double square introduces √5; √5 makes φ unavoidable; φ and √3 together allow Mars-scaled lengths to propagate cleanly from chamber to pyramid. π enters where circular equivalence is implied, particularly when dimensions are expressed in metres or when linear measures are related to perimeters.

It is important to stress that this geometry does not appear to have been chosen in order to encode Mars. Rather, the situation seems reversed. Because Mars’s cycles already sit so near to key solar–lunar ratios, the geometry required to stabilise them emerges almost automatically. The double square, √5, φ, √3, and π are not decorative overlays, but structural responses to a set of naturally converging numbers.

In this sense, Mars functions as a mediating quantity. It links sidereal and synodic time, bridges chamber-scale and pyramid-scale dimensions, and converts astronomical cycles into stable architectural form. Geometry does not impose order on these relationships; it resolves them. Architecture does not symbolise the cycles; it gives them a place to settle.

What we see at Giza, then, is not a symbolic exaltation of Mars, but a practical one. Mars is the planet whose cycles most readily invite geometric consolidation, and it is this numerical circumstance, rather than myth or ritual, that appears to underlie its prominence within the King’s Chamber and beyond.

686.980 x 3 / 2 x √5 x 10 / 29.53059 = 780.276

If we take Petrie’s measured width of the King’s Chamber as a unit, the double-square geometry immediately yields √5 through its diagonal, and therefore the golden ratio φ. Using the chamber width of 206.1 inches, the expression (206.1 × √5 + 206.1) / 2 is simply the width multiplied by φ.

When this φ-scaled width is then multiplied by √3 and by a factor of ten, the result is 5,775.99 inches—essentially the reconstructed original height of the Great Pyramid in inches. In compact form:

Width of the King’s Chamber × φ × √3 × 10 ≈ Height of the Great Pyramid.

Since the width of the King’s Chamber itself derives from a simple decimal reduction of Mars’s sidereal orbital period, the same relationship can be expressed in another way:

Mars sidereal period × 3 × φ × √3 ≈ Height of the Great Pyramid.

The height of the Great Pyramid is, in turn, very closely approximated by 10,000 / √3 inches. Rearranging this relationship allows Mars’s sidereal period to be written as:

10,000 / (9 × φ) = 686.70 days.

The 10 000 in the equation can be interpreted as the number one, the concept of oneness. The golden ratio (φ) is a generative ratio associated with growth and life, and √3 as the geometry of mediation and intersection, and the number 9 as a harmonic multiplier. Together these elements yield Mars’s orbital period in days and re-emerge, scaled and transformed, in the proportions of the King’s Chamber and the height of the Great Pyramid. In this light, the prominence of Mars within the King’s Chamber may be understood as the natural consequence of a harmonic system in which number, geometry, and planetary motion were regarded as expressions of a single creative order. In such a system, it is hardly surprising that Mars, expressed through unity, φ, and the harmonic power of nine, should occupy a privileged position within the King’s Chamber, a space that appears to translate the dynamics of the heavens into enduring stone.

The sequence of equations presented here is best understood as a procedural chain: a set of operations applied repeatedly to one initial quantity, generating a family of related architectural dimensions across the Giza plateau. The entire sequence begins with a single astronomical value: Mars’s sidereal orbital period, expressed in days.

The Mars–√5 seed is multiplied by simple integers (such as 10 or 80), or by calendrical scaling factors, notably 10 000 / 254, where 254 represents the number of sidereal lunar months in a Metonic cycle. Applying these scalings produces, in turn:

the distance between the centres of the Great Pyramid and the Third Pyramid,

the side length of the Great Pyramid,

the length of the Great Giza Rectangle,

and the base sides of the Second and Third Pyramids.

At each step, the resulting value is compared directly with Petrie’s measurements, and the difference is explicitly stated.

Where pyramid heights are introduced, they are obtained through purely geometric relationships, for example, multiplication by 2/π or division by φ, rather than by inserting new astronomical periods.

The sequence concludes with the Queen’s Chamber, which appears to function as a metre-scale analogue of the Great Pyramid’s vertical dimension. Here, values that appear elsewhere in inches re-emerge in metres, mediated by √3, π, φ, and lunar–solar ratios. This does not introduce a new system, but rather confirms the flexibility of the existing one across unit systems. Although the equations are written from the King’s Chamber outward, the system is reversible.

Taken as a whole, this series of equations demonstrates that a single Mars-derived quantity, once passed through the geometry of the double square and scaled using a small and consistent set of calendrical factors, is sufficient to reproduce the principal dimensions of the Giza complex within narrow tolerances.

What matters is not any individual numerical match, but the coherence of the system: the same operations recur, the same constants reappear, and the same astronomical and geometric ideas connect chamber-scale dimensions to site-scale architecture. The result is a structure in which time, geometry, and measure are not separate domains, but different expressions of a single organising logic.

Conclusion

What is being proposed here is that the Giza designers worked inside a coherent numerical framework, one in which planetary periods, lunar cycles, solar rhythms, and long-term precessional time could be rendered in stone through repeatable operations: multiplication, division, a handful of ratios, and a small set of geometric operators.

The same numbers return again and again when time is translated into length using consistent rules, sometimes through the inch as a “day-number,” sometimes through the metre as a solar–lunar hybrid, or the Saxon foot, sometimes through the implicit geometry of √3, √5, π, and φ. This has consequences for the way we think about units at Giza. Modern discussions of ancient Egyptian measurement often begin with the cubit, as though it were a fixed physical standard imposed uniformly across all dimensions. Yet Petrie himself noted that the most carefully set-out part of the pyramid may have been the base of the King’s Chamber, and he observed that the implied cubit value can be recovered most cleanly from that part. He gives the squared chamber dimensions as:

Width 206.12 ± 0.12 ≈ 100 cubits of 20.612 ± 0.012

Length 412.24 ± 0.12 ≈ 200 cubits of 20.612 ± 0.006

Height 230.09 ± 0.15 ≈ 125 cubits of 20.580 ± 0.014

He also writes:

“Probably the base of the chamber was the part most carefully adjusted and set out; and hence the original value of the cubit used can be most accurately recovered from that part… 20.632 ± .004… certainly the best determination… from the Great Pyramid.”

But Petrie’s own tables show that other features imply slightly different values. Rather than undermining the measurements, this variability may point to a subtler reality: the cubit is neither primary nor fixed. The King’s Chamber is a good place to see this. It is often described as a simple 10 × 20 cubit space, true enough in form, since it is a double square. But the double square is not just a rectangle: it is a generator. Its diagonal introduces √5 automatically, and with √5 comes φ. The chamber’s plan is anchored by Mars’s sidereal period expressed in days and read as inches: Mars × 3/10 gives the chamber width; Mars × 6/10 gives the length; and the diagonal relation (√5) becomes part of the chamber’s arithmetic. The cubit, in this setting, can be reinterpreted as whatever length allows the chamber to hold a clean integer count while still remaining faithful to the astronomical seed. It is not arbitrary; it is contextual.

Seen this way, it becomes meaningful that several independent definitions of a cubit cluster near the King’s Chamber scale. For example, Mars’s sidereal period converted to inches and scaled by 3/10 yields a value close to 20.61 inches. The inverse of φ, scaled by 100/3, yields a similar value. The ratio between the tropical and lunar years, scaled by 20, produces another nearby value. The cubit hovers where it should hover if it is acting as an interface between Mars, solar–lunar reconciliation, and the φ/√5 geometry latent in the chamber itself.

The same “unit as role” approach also makes sense of the appearance of π in metre-scale readings. Using Petrie’s measurements, the perimeter of the King’s Chamber in metres sits close to 10π, suggesting that circle geometry is not merely decorative but functional: a way of normalising rectilinear architecture against circular time. Schwaller de Lubicz’s old suggestion, that the royal cubit might be understood in relation to π (for example, π/6 metres), is not offered here as a final answer, but it does belong to the same family of ideas: units emerging from geometry, rather than geometry being forced into units.

And this, finally, returns us to the central claim of the article. The most striking feature of the “planets at Giza” argument is not any single match, but the way the site behaves like a system. The same conversions and operators recur, lunation factors, Metonic/Saros ratios, √3, √5, φ, π, across multiple scales: chamber, pyramid, plateau rectangle. The system is often reversible: one can enter at a planetary product and arrive at a ground-plan dimension, or enter at a chamber dimension and climb back to an astronomical synthesis. This is exactly what one would expect if the builders were not merely laying out monuments, but constructing a computable landscape: a place where the motions of the heavens could be handled, reconciled, and scaled—an architecture of time.

If so, then Giza is like a game: the translation of complex celestial order into a small repertoire of operations. The inch, the cubit, and the metre can be seen as different registers within the same framework, different ways of letting time appear as length. And the planets, fast and slow, sidereal and synodic, are not ornaments to the design. They are among its organising principles.

One final observation may be worth making. The numerical and procedural character of the system reconstructed here, its reliance on algorithmic chains, reversible operations, and abstract mediation between cycles, does not sit easily with what we typically associate with Old Kingdom Egyptian intellectual culture, at least as it is represented in the surviving textual record. Egyptian cosmology, as we know it, is rich, symbolic, and deeply structured, but it is rarely explicit in its use of formal calculation as an organising principle.

This does not mean that such a system could not have existed in Egypt, nor that the builders lacked mathematical sophistication. It does suggest, however, that the framework expressed at Giza may preserve a mode of thinking whose roots are earlier, broader, or differently transmitted than the texts that have come down to us. Whether this reflects the loss of a technical tradition, the inheritance of ideas from a deeper past, or a synthesis later re-articulated in Greek philosophy is a question that cannot be settled here. What can be said is that the architecture itself behaves as though it were designed to think, to compute, reconcile, and stabilise cosmic time, regardless of how that thinking was later explained in myth.

What is being proposed here is that the builders of Giza were responding to order in the cosmos, and that this response took the form of number, geometry, and measure. The pyramids need not be read as monuments to power alone, but as works of alignment, attempts to live, build, and measure in accordance with an intelligible structure already present in the universe. In Egyptian thought, this structure was known as Maʿat: not merely truth or justice, but right proportion, balance, and the correct ordering of things. Maʿat was not imposed by decree; it was maintained through attentiveness and right action. In Greek terms, one might speak instead of logos: the rational pattern by which the cosmos is ordered and rendered intelligible. Though culturally distinct, both ideas point to the same conviction, that the universe is not arbitrary, and that its order can be apprehended through number, ratio, and recurrence.

In the Platonic account, the Demiurge does not animate the Earth itself, but sets the heavens in motion. The divine order is therefore visible above all in the sky: in the revolutions of the planets, the cycles of the Sun and Moon, and the slow turning of precession. These motions are lawful, repetitive, and measurable. They constitute the active expression of cosmic order. Human beings possess the capacity to observe, calculate, and translate. The work at Giza can be understood as an exercise in that translation. Through geometry, celestial motion is rendered as spatial proportion; through number, time is made present as length. The pyramids do not imitate the heavens pictorially, nor do they mythologise them. Instead, they restate celestial order in terrestrial form, using a disciplined arithmetic that allows planetary periods, lunar cycles, and long-term cosmic rhythms to be held together within a single coherent framework.

Seen this way, the planetary correspondences identified across the Giza plateau are the structural consequences of working consistently within such a framework. The recurrence of Mars, the Moon, the Metonic cycle, precession, and key geometric irrationals is not evidence of obsession, but of constraint. Once certain astronomical quantities are chosen as fundamental, and once geometry is allowed to do its work, the system largely generates itself. The small residual mismatches that remain are not failures of the model, but signatures of its realism, what one would expect when continuous celestial motion is compressed into finite, buildable architecture.

This perspective also reframes the question of units. Rather than beginning with a fixed cubit and deriving everything else from it, the evidence suggests that measure at Giza was emergent. Units appear to arise from the interaction of geometry and cycle, adapting to different roles within the same numerical ecology. Measure, in this sense, is not an arbitrary convention but a mediator between the human scale and the cosmic one.

Why, then, build the pyramids at all? One possible answer is that they functioned as a justification of a way of life. To build in accordance with Maʿat, or logos, was not merely to construct well, but to affirm that human society itself ought to be ordered in resonance with the larger order of the cosmos. The pyramids stand as celebrations of the fact that the universe is countable, intelligible, and harmonically structured, and that human beings are capable of recognising this and responding appropriately.

In this light, Giza need not be seen as an assertion of human dominance but on the contrary as an act of attentiveness. They stand as a declaration, carved into the landscape, that to live well is to align oneself and one’s works, albeit necessarily imperfectly, with the enduring order written in the heavens.

Thank you to Jim Wakefield and to Dane Quirk.

Notes

Timaeus, Plato, 360 B.C.E, 39d, Translated by Benjamin Jowett, https://classics.mit.edu/Plato/timaeus.html

Cornford, Francis Macdonald, 1937, Platos Cosmology, pp92-93

https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.221748/page/n111/mode/2up

Flinders Petrie, WM, The Pyramids and Temples of Gizeh

4. Ibid.

Comments