98. A Stonehenge Dataset

- M Campbell

- Dec 24, 2025

- 22 min read

Updated: Dec 26, 2025

The paper “Units of Measurement in Late Neolithic Southern Britain” by Andrew Chamberlain and Mike Parker Pearson (2007) represents one of the more cautious modern attempts to identify units of measure in prehistoric monuments. The authors' approach is statistical and archaeological: to infer possible quanta of measurement by examining regularities in the diameters of earthworks and post-hole rings around Stonehenge and nearby sites such as Durrington Walls and Woodhenge. They find two base units: a long foot of 1.056 English feet (12.67 inches) and a short foot of 0.96 English feet (11.52 inches), related by a ratio of 11:10 (a ratio, which mirrors the relationship between the Saxon and English feet). Focusing on accurately surveyed diameters of circular earthworks and settings of pits, postholes, and stones, features less likely to have shifted than the megaliths themselves, they tested for recurring modular lengths that might reveal underlying “quanta” of design.

While the authors were cautious about over-interpreting limited data, they concluded that these consistent modular patterns across multiple sites strongly imply deliberate use of measured planning, perhaps employing interrelated units of measure adapted to different constructional or symbolic contexts.

These are interesting results, and the authors deserve credit for grounding their conclusions in careful data. Yet their interpretation of what such results imply is remarkably restrained. Chamberlain and Parker Pearson explicitly state that the symmetry and astronomical alignments of prehistoric monuments might have arisen without any fixed system of measure, perhaps through regular pacing, trial and error, or purely visual judgement. This view, seemingly common in modern archaeology, effectively attributes the geometry of Stonehenge to accident, or at least to intuition without mathematics.

That position, to my mind, reflects less the evidence on the ground than a deeply ingrained cultural assumption: that our prehistoric ancestors were incapable of systematic reasoning, or that sophisticated geometry and metrology belong only to literate or “civilised” societies. This is a curiously persistent bias toward prehistoric peoples as spiritually benighted and intellectually primitive. It is a view that survives, even within scientific discourse. The builders of Stonehenge are admired for their engineering, but denied mathematical intelligence.

The statistical search for a “quantum of measurement”, pioneered by Alexander Thom and repeated by others since, is an attempt to find a pattern without necessarily taking into account its geometric basis. It assumes the unit will be an arbitrary integer of some forgotten foot or yard. This approach would make it difficult to find evidence of geometric or harmonic ratios, circles, constants such as π and √3, or non-integer numbers derived from astronomical patterns in time. To rely only on statistical peaks may be to miss something important.

The alternative is to begin from geometry itself, seeing the plan not as a cloud of numbers to be scanned for multiples of some random integers, but looking for patterns in the proportions and ratios, and perhaps indications of astro-geometry. The inch may be the most revealing key through which to read these ancient plans. When expressed in inches, rather than in “long” or “short” feet, the monuments’ dimensions often align precisely with harmonic ratios, such as π, φ, 2, 3, 4, and the lunar and solar values. The metre, too, emerges as part of this larger story, the modern metric system being based on a revival of an ancient measure of the Earth itself.

In this article, I have taken the dimensions recorded by Parker Pearson and Chamberlain and re-expressed them in inches, and looked at the proportions in order to understand their underlying structure. I try to look for ways in which to interpret the proportions, and then see in which unit these numbers are best expressed. In practice, this involves identifying the key base elements (diameter, circumference, etc) and testing whether they are related by simple whole-number ratios or by constants such as π, φ, √2, or √3, or by lunar, planetary and solar values. My interpretation of measurements at Giza, at Khorsabad, and at various megalithic sites suggests that the English inch and foot, the Saxon foot, the metre and the Egyptian royal cubit were relevant to the design of these structures, but that the inch, in particular was key. The monument is treated as a coherent design, where each circle and distance potentially expresses a geometric or astronomical relation to a foundational unit.

By reading the data presented by Chamberlain and Parker Pearson in this way, we can test whether its builders were indeed part of a broader, sophisticated scientific tradition, one that united considerations of weight, volume, time, and geometry long before such interrelations were rediscovered in the modern age. Chamberlain and Parker Pearson's paper features three tables with data, and so this article looks at each one of these tables and looks for patterns in proportions first, then in inches and other units.

The table below gives the measurements, as per the Chamberlain and Parker Pearson paper, and the dimensions included in their study are diameters for: the counterscarp bank, the ditch, at the lowest point, the bank, the aubrey holes, the Z holes, the Y holes, the sarsen circle and the bluestone circle.

Table 1. Based on table in the Chamberlain & Parker Pearson paper, with added columns (in blue). Interesting values are in bold, those which are especially interesting in red, the others in blue. Scroll to the right for extra columns.

Phase | Structural Component | Diameter (m) | Diameter (stat. ft) | Diameter (‘long’ ft) | Modular Diameter | Absolute Error | Diameter in Inches (converted from value in feet) | Diameter in Inches (converted from value in metres) | Diameter in inches × π (circumference) | Diameter in inches ÷ (6×√3×365.25) | Diameter in inches ÷ 365.25×√3 | Diameter in inches ÷ 365.25 × 8 | Circumference in inches ÷ (√3×365.25) | Diameter in inches x 3 x √3 ÷ (2000 π) | Diameter in metres x 100 ÷ 29.53059 | |

1 | Counterscarp bank | 116.00 | 380.58 | 360.40 | 360.4 | 0.4 | 4566.96 | 4566.93 | 14 347.42 | 1.203 | 21.657 | 100.03 | 22.6789 | 3.777 | 392.8130 | |

1 | Ditch (lowest point) | 106.28 | 348.69 | 330.20 | 330.0 | 0.2 | 4184.28 | 4184.25 | 13 145.20 | 1.102 | 19.842 | 91.65 | 20.779 | 3.460 | 359.89799 | |

1 | Bank | 96.60 | 316.93 | 300.12 | 300.0 | 0.12 | 3803.16 | 3803.15 | 11 947.94 | 1.002 | 18.035 | 83.30 | 18.886 | 3.145 | 327.1184 | |

1 | Aubrey Holes | 87.05 | 285.60 | 270.45 | 270.0 | 0.45 | 3427.20 | 3427.17 | 10 766.75 | 0.903 | 16.252 | 75.06 | 17.019 | 2.834 | 294.7791 | |

3vi | Y holes | 53.57 | 175.76 | 166.44 | – | – | 2109.12 | 2109.06 | 6625.79 | 0.556 | 10.001 | 46.19 | 10.4733 | 1.744 | 181.4051 | |

3vi | Z holes | 38.57 | 126.55 | 119.84 | 120 | 0.16 | 1518.60 | 1518.50 | 4770.52 | 0.400 | 7.201 | 33.26 | 7.541 | 1.256 | 130.6103 | |

3ii | Sarsen circle | 30.69 | 100.68 | 95.34 | – | – | 1208.16 | 1208.27 | 3795.88 | 0.318 | 5.730 | 26.46 | 6.000 | 0.99923 | 103.9261 | |

3v | Bluestone circle | 24.25 | 79.56 | 75.34 | – | – | 954.72 | 954.72 | 2999.35 | 0.252 | 4.527 | 20.91 | 4.741 | 0.7895 | 82.1182 |

Table 2: Ratios between rings

Between rings | Ratio (outer ÷ inner) | Approx. simple fraction |

Counterscarp bank : Ditch | 1.091 | 12 : 11 |

Ditch : Bank | 1.100 | 11 : 10 |

Bank : Aubrey Holes | 1.110 | 10 : 9 |

Aubrey : Y holes | 1.625 | 13 : 8 |

Y : Z holes | 1.389 | 25 : 18 |

Z : Sarsen | 1.257 | 5 : 4 |

Sarsen : Bluestone | 1.266 | 19 : 15 (≈ 4 : 3) |

At a glance, the following ratios appear between the values in table 1:

The data from Chamberlain and Parker Pearson’s first table provides the measured and modular diameters for the major concentric components of Stonehenge, ranging from the outer counterscarp bank (116 m) to the inner bluestone circle (24.25 m). When these same values are expressed in inches, π-derived circumferences, and through various harmonic and astronomical ratios, several possible relationships emerge:

The counterscarp bank is 100.03 x 365.25 / 8 inches in circumference. Another reading is 72 x √3 x 365.25 / 10 inches.

The ditch (lowest point) diameter is close to 360 x 29.53059 / 100 metres. It is 3.46 times larger than the Sarsen circle diameter, and this number is interesting in that a draconic month is 346.62 days.

The bank diameter is 365.25 x 6 x √3 inches. The diameter is close to 200 x 19 inches, and 19 is the number of years in a Metonic cycle. In metres it can be understood as 12 x 12 x 3 / 10 x √5. Its circumference is close to 12 000 inches.

The Aubrey holes diameter is approximately 3/4 of the counterscarp bank diameter, so 365.25 x 300 / 32 inches. The diameter is also close to 75 / 8 x 365.25 inches.

The Y holes diameter is 10 x 365.25 / √3 inches. The Y holes diameter x 72 / 100 gives the Z holes diameter. There is also an exactly 15 metre difference between the diameters of the Y and Z holes. The bank diameter multiplied by 24 / 25 and divided by √3 gives the Y holes diameter.

The Z holes diameter is approximately 4 / 10 times the bank diameter, and Z holes diameter ≈ 0.4π × Sarsen diameter (−0.009%). The Z holes diameter is also almost exactly 3 times smaller than the counterscarp bank diameter. In inches, the Z holes diameter is equal to 24 x √3 x 365.25 / 10. Alternatively, they can be read as 100 x 365.25 / 24 inches.

The Sarsen circle diameter is 6 x 365.25 x √3 / π inches. The diameter is also close to 2000 π / (3 x √3) inches. The Sarsen circle diameter 4 / 10 x π gives the Z holes diameter. The Sarsen circle diameter x π is approximately equal to the diameter of the bank.

The Bluestone circle circumference is very close to 3000 inches.

Table 3: Fits and errors (using the paper’s diameters)

All “actual” inch values are those I converted from the metres column in table 1. Predicted values use the formula shown in the second column. The "proposed formula" column contains possible interpretations of the data. Data given in inches, except for the ditch, in metres.

Feature (what) | Proposed formula | Predicted | Actual | Abs. diff | % diff |

Counterscarp (Diameter) | 100.03×365.25/8 | 4,566.99 in | 4,566.93 in | +0.06 | +0.001% |

Counterscarp (Diameter) | 72×√3×365.25/10 | 4,554.95 in | 4,566.93 in | −11.98 | −0.262% |

Ditch (Diameter, metres) | 360×29.53059/100 | 106.310 m | 106.28 m | +0.030 m | +0.028% |

Bank (Diameter) | 365.25×6×√3 | 3,795.89 in | 3,803.15 in | −7.26 | −0.191% |

Bank (Diameter) | Counterscarp (diam.) x 5 / 6 | 3,805.775 in | 3,803.15 in | +2.625 | +0.069% |

Bank (Circumference) | ≈ 12,000 | 12,000.00 in | 11,947.94 in | +52.06 | +0.435% |

Aubrey (Diameter) | ¾ × Counterscarp | 3,425.20 in | 3,427.17 in | −1.97 | −0.057% |

Aubrey (Diameter) | 365.25 x 300 / (4 x 8) | 3,424.22 in | 3,427.17 in | −2.95 | −0.086% |

Y holes (Diameter) | 10×365.25/√3 | 2,108.73 in | 2,109.06 in | −0.33 | −0.014% |

Y holes (Diameter) | Counterscarp x 8 /(10 √3) | 2,108.77 | 2,109.06 in | -0.29 | -0.014% |

Y holes (Diameter) | Bank diameter x 24 / 25 x 1 / √3 | 2103.896 in | 2,109.06 in | -5.16 | -0.25% |

Z from Y (Diameter) | Y×0.72 | 1,517. in | 1,518.50 in | −0.02 | −0.002% |

Z (Diameter) | 0.4×Bank (diam.) | 1,521.26 in | 1,518.50 in | +2.76 | +0.182% |

Z (Diameter) | Counterscarp/3 | 1,522.31 in | 1,518.50 in | +3.81 | +0.251% |

Z (Diameter) | 24×√3×365.25/10 | 1,518.32 in | 1,518.50 in | −0.18 | −0.012% |

Z (Diameter) | 100×365.25/24 | 1,521.88 in | 1,518.50 in | +3.38 | +0.222% |

Z (Diameter) | 0.4π×Sarsen (diam.) | 1,518.36 in | 1,518.50 in | −0.14 | −0.009% |

Sarsen (Diameter) | Y holes x 9 / (5π) | 1209.06 in | 1208.27 in | +0.79 | +0.065% |

Sarsen (Diameter) | 2000π/(3√3) | 1,209.20 in | 1,208.27 in | +0.93 | +0.077% |

Bank (Diameter) | π×Sarsen | 3,795.89 in | 3,803.15 in | −7.26 | −0.191% |

Bluestone (Circumference) | ≈ 3,000 | 3,000.00 in | 2,999.35 in | +0.65 | +0.022% |

The ratios present in the table above can be simplified, as per the diagram below.

What can the dimensions tell us? The first interesting thing to note is that two of the measures are close to multiples of 1000 inches.

Bluestone circumference ≈ 3×1000 in (+0.022%).

Bank circumference ≈ 12×1000 in (+0.435%).

In addition, the bluestone diameter multiplied by Phi squared also gives an interesting result in inches: 954.72 x 2.618034 = 2499.49, which is practically 2500 inches. The values seem to imply a natural base module of 1 000 inches, a scale that recurs elsewhere in the monument.

Sarsen Circle diameter resolves to 2π / (3√3) × 1 000 = 1 209.200 inches.

Sarsen Circle circumference resolves to 2π² / (3√3) × 1 000 = 3 798.813 inches.

Bank circumference resolves to 2π³ / (3√3) × 1 000 = 11 934.321 inches.

Bank circumference resolves to π³ / (6√3) × 1 000 = 2 983.580 inches.

This can be interpreted as a starting point of 1000 inches generating ther measures, through geometry, and time cycles, even if no obvious measure on the ground is 1000 inches long. This can be seen elsewhere, for example at Giza for example, the height of the Great Pyramid can be interpreted as 10 000 / √3 inches, and the length of the rectangle which encompasses the three main pyramids at Giza is 1 000 000 / 28 inches.

The Sarsen circle diameter can also be defined by 6 x √3 x 365.25 / π inches, which is in fact a slightly better fit to the data. Four of the key circles line up with these values, very small errors (all under ~0.2% compared to the measured inch values from Chamberlain & Parker Pearson’s Table 1):

Bank diameter ≈ π × Sarsen diameter (−0.191%).

Z-holes diameter ≈ 0.4π × Sarsen diameter (−0.009%).

Y-holes diameter matches the solar-geometric form 10×365.25/√3 inches (−0.014%). The Y-holes diameter is close to 5π /9 x Sarsen diameter.

Aubrey sits at ¾ of the Counterscarp (−0.057%), giving the 4:3 outer pair.

What these figures seem to imply, overall, is that there are precise integer and irrational ratios between elements of Stonehenge, and that these seem to reflected in values in inches.

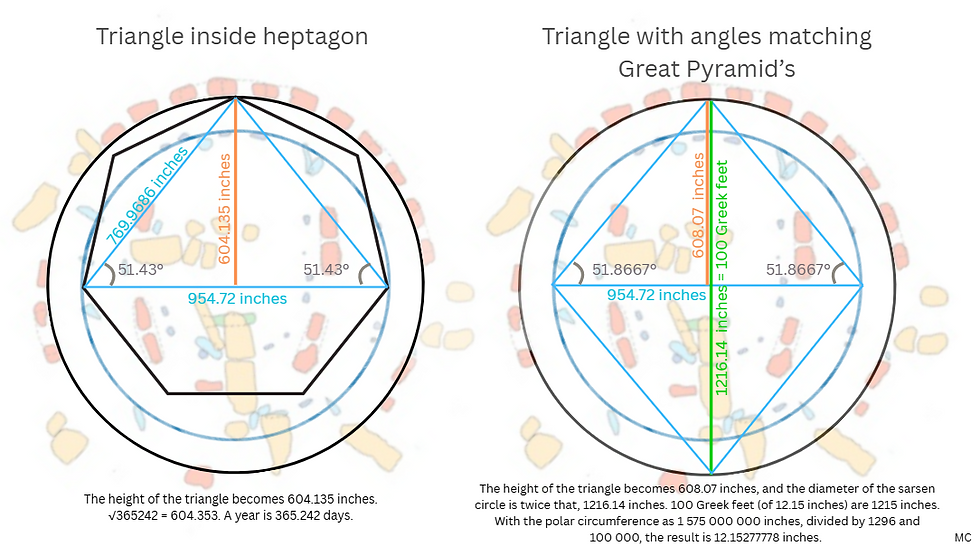

The diameter of the Sarsen Circle, as measured by Chamberlain and Parker Pearson, is approximately 30.69 metres or 1 208.31 inches. A closely related theoretical value is given by the expression 2000π/(3√3), which yields 1 209.2 inches. When an equilateral triangle is inscribed within a circle of this size, each side measures 1000π inches and the resulting perimeter is exactly 1000π inches. The height of this triangle, 2√3 / (1000 π), is 906.9 inches. This is strikingly close to one-tenth of the base length of the Great Pyramid at Giza, measured by Petrie at 9 068.8 inches. A square whose side is equal to the height of the inscribed equilateral triangle at Stonehenge is therefore a geometrically scaled counterpart of the Great Pyramid’s base. Both monuments can thus be interpreted as expressions of the same circle–triangle proportional system, governed by the ratio 2000π/(3√3), though at markedly different scales and in different cultural contexts. A further resonance is found in the bluestone circle, whose diameter of 24.25 metres (954.724 inches) corresponds to the expression obtained by dividing the triangle’s perimeter by π and multiplying by three, suggesting a coherent internal proportionality within the Stonehenge complex itself. It is almost ironic that the perimeter of the triangle is 1000π inches and the circumference of the bluestone circle is 3000 inches, when you might imagine it to be the reverse, the triangle not containing pi.

This circle–triangle framework provides a natural bridge into the astronomical logic embedded within Stonehenge. The proportional system implied by the Sarsen Circle’s diameter and the derived equilateral geometry accommodates numerical values that recur in lunar and solar cycles, notably those associated with synodic, sidereal and draconic months. When the triangle’s perimeter, height and radius are converted into lunar-month or solar-year units, they echo relationships familiar from Metonic, draconic and eclipse cycles. In this sense, the geometry of the Sarsen ring functions not only as a spatial design principle but as a container for temporal harmonies, suggesting that the builders may have used circular and triangular forms as a means of translating the rhythms of the sky into architectural proportion.

Looking more closely at the Giza connection

The Sarsen circle diameter, if taken as (2π / (3√3) × 1 000 ≈ 1 209.2 inches:

multiplied by 30 / (2π ) gives the height of the Great Pyramid

multiplied by 30 gives the Great Pyramid perimeter, or x 29.53059 x 254 / 1 000 x 4.

multiplied by 29.53059 x 223 / 235 gives the perimeter of the second pyramid

multiplied by 223 x 29.53059 x π / (47² x 2) gives the height of the second pyramid

multiplied by 29.53059 gives the length of the rectangle formed by the three great pyramids (the outer corners of the great and third pyramids)

multiplied by 29.53059 x 9/11 gives the width of this rectangle

multiplied by 29.53059² / 254 gives the side of the third pyramid

multiplied by 29.53059² / (254 x 1.61803) gives the height of the third pyramid

π / √3 relates circular to triangular geometry — the ratio between the circumference of a circle and the perimeter of an inscribed equilateral triangle.

29.53059 converts that geometry into temporal measure, the length of one lunation.

223 / 235 encodes the Saros–Metonic ratio, the long-term reconciliation of solar and lunar years used in eclipse prediction.

254, the number of sidereal months in a Metonic period, converts the same geometry into linear distances.

The factor 2π / (3√3) is the geometric ratio that links a circle’s circumference to the side of a hexagon inscribed within it, the bridge between the circle and the triangle, and therefore between angular and linear geometries. Remarkably, it is also the same factor that appears when astronomical cycles are compared:

solar year × draconic year÷lunar year ≈ 20π x synodic month (lunation) ÷ (3 x √3).

These numbers unite the sun, moon, and nodal cycles in the same geometric language. If we take just 2π / 3, dropping the square root of three in the denominator, then there is another important correspondence: 2π / 3 is almost equivalent to 10⁸ / (19 x 25 920 x 29.46 x 11.86 x 1.88 x 0.615 x 0.24), to 4 decimal places. What this series of numbers is a combination of many cycles:

Metonic cycle: 19 years

Axial precession: 25 920 years (traditional value)

Mercury 0.24 years

Venus 0.615 years

Mars 1.88 years

Jupiter 11.86 years

Saturn 29.46 years

So that:

Metonic x precession x Saturn x Jupiter x Mars x Venus x Mercury / 10⁸ = 3 / (2π )

(Or 19 x 25 920 x 29.46 x 11.86 x 1.88 x 0.615 x 0.24 / 10⁸ x π = 3 / 2)

In music, the 3/2 ratio is called a perfect fifth. Moreover, the 2/3 ratio, combined with pi and the square root of three, serve to bridge the values derived from observing the civil year, the draconic year, the lunar year and a lunation, expressed in days, as well as the number of lunations per year. (see below)

.

The Sarsen diameter is also close to another important value in inches: 1 000 000 / (28 x 29.53059) = 1209.4 . This unites the number of days in a lunation (29.53059) to the number 28, a key number, being a rounded up value of the number of days in a sidereal month, and 4 x 7, the number of days in four weeks. 28 is perfect number. It also links other celestial cycles in a single number. The Great Pyramid of Giza, measuring approximately 280 Egyptian royal cubits in height (where 1 cubit is 20.62857 inches or 0.5239657 meters), might imply a connection between its dimensions and the number 28. This number is associated with the lunar month, as the sidereal month is just over 27 days and rounds up to 28. Moreover, 28 divides easily into four weeks of seven days, a structure central to ancient timekeeping. Some ancient cultures also divided the Zodiac into 27 or 28 segments, known as lunar mansions, which parallel divisions of the cubit rod and underscore the lunar significance of 28. Beyond astronomy, the number 28, like the number 6, is a "perfect number," meaning it equals the sum of its divisors (1, 2, 4, 7, 14). This fact deepens its symbolic role in ancient numerology, where it may have represented cosmic harmony. The fraction 1 / 28 holds additional interest when applied to astronomical cycles. For instance, the expression 2 π x 29.53059 / (3000 x √3), with 29.53059 representing the lunation period (number of days in a lunar month), suggests further astronomical connections when these cycles are interpreted through irrational numbers. Similarly, calculating a yuga of 4 320 000 years multiplied by 3 x √3 / (200 π) approximates the Giza rectangle’s length in inches as 35 726.1124, a value close to the measurement given by Petrie at 35 713.2 inches, and intriguingly near 1 000 000 / 28 ≈ 35 714.2857 inches. Interestingly, when dividing a yuga of 4 320 000 years by each planet’s orbital period, lunar cycles, precession, and the Metonic cycle of 19 years, the result approximates 1/28, or 2 π x 29.53059 / (3 √3) closely:

4 320 000 / (0.24 x 0.615 x 1.88 x 11.86 x 29.46 x 0.0748 x 25920 x 19) ≈ 2 π x 29.53059 / (3 √3)

Thus, dividing 100 000 000 earth years by these same cycles, the result nears exactly 28:

1 000 000 / (0.24 x 0.615 x 1.88 x 11.86 x 29.46 x 0.0748 x 25 920 x 19) = 27.999364

We've seen that it is crucial at Stonehenge, and it also fits quite well with various measurements at Giza. Across the entire Giza suite, when Petrie’s measured values are scaled by their respective geometric constants, each converges on about 1209 inches ± 1.5, essentially the Stonehenge Sarsen diameter. That can’t easily be coincidence: it shows the same ratio of π, √3 and lunar constants (29.53059, 235, 223) yields the same scale factor in both monuments.

In symbolic terms, 1209 inches seems to operate as a modular bridge, the point where solar (365.25), lunar (29.53) and geometric (π and √3) cycles find a common numeric harmony. In both the Giza layout and Stonehenge’s inner architecture, it marks the shift from counting and geometry to the representation of time.

Element | Computed | Petrie (in) | % diff | Connection to Sarsen circle diameter of 1 208.27 in (Chamberlain & Parker Pearson). Petrie value multiplied by: | Difference between Petrie's value for Giza and the calculated value approximating the Sarsen diameter, in inches | |

Great Pyramid side | 5 000 π / √3 | 9068.99 | 9068.8 | +0.00% | x 4 / 30 = 1209.173 | 0.903 |

Great Pyramid height | 10 000/ √3 | 5773.5 | 5776 ±7 | +0.05% | x 4 / 30 x π / 2 = 1209.723 | 1.453 |

Great Pyramid perimeter | 20 000 π/√3 | 36 726 | 36 275 | +1.2% | x 1 / 30 = 1209.167 | 0.897 |

Second Pyramid side | π / (√3 x 3) x 29.53059 x 1000 x 223 / 235 | 8471.2 | 8474.9 | +0.04% | x 1 / 7 = 1210.7 | 2.43 |

Third Pyramid side | 2 000π/(√3 x 3) x 29.53059² / 254 | 4151.5 | 4153.6 | +0.05% | x 254 / 29.53059² = 1209.802 | 1.532 |

Giza Rectangle length | 5 000 000 π / (√3 x 254) or 1 000 000 / 28 | 35 705 or 35 714.2857 | 35 713.2 | +0.02% | x 1 / 29.53059 = 1209.363 | 1.093 |

Giza Rectangle width | 32/3 π x 29.53059² | 29 223 | 29 227.2 | +0.01% | x 11/(9 x 29.53059) = 1209.665 | 1.395 |

When the classical and harmonic formulations of the Giza pyramids are expressed in inches, using the same π and √3 framework that fits Stonehenge, the resulting values cluster around 1209 inches (≈ 30.7 m). This is the measured diameter of the Stonehenge Sarsen Circle (1 208.27 in, Chamberlain & Parker Pearson 2007). This system turns cycles of time into expressions of space, uniting lunar months, solar years, other cycles, and geometric forms into one continuous measure. Taken together, these patterns suggest not an isolated invention but a shared metrological logic, grounded in natural constants, cyclical time, and the enduring intuition that measure, when properly conceived, is a reflection of cosmic order.

The Sarsen Circle diameter of 30.69 m (1 208.27 inches) appears not only as the geometric core of Stonehenge but also as a constant that links directly to the classical architecture of Giza. When the same geometric ratios used to express the Great Pyramid’s side, height, and perimeter are rescaled by their own constants of π, √3, 29.53059, 223, and 235, every value converges on ≈ 1209 in ± 1.5, matching the Stonehenge Sarsen diameter, which can be interpreted as:

2000π / (3 √3) ≈ 6 √3×365.25 / π

The first expression is purely geometric, relating the circumference of a circle to the side of an inscribed hexagon, while the second is astronomical, expressing the solar year (365.25 days) through the same constants of π and √3. Their near-identity defines 1209 inches, the precise Sarsen diameter. In this way, the number functions as a bridge between space and time, between geometry and the calendar. Combinations of time cycles linking the sun, the moon and the planets all come together with these constants, more or less approximately. For example:

365.242199 x 346.62 x 100 / (354.36708 x 29.53059) = 1209.794

and 2000 π / (3 x √3) = 1209.2, almost the same value.

2000 π /(3√3) approx equal to 6 x √3 x 365.25 / π

2000 π ² / 54 = 365.541 or 37 x π ² = 365.175

And 365 x 346.6201 / (354.36708 x 29.53059) is almost equal to π / √3 x 20 / 3. The number of lunations per year is close to π /√3 x 300 / 44

Each constant within this system plays a specific role:

π / √3 links the circle to the equilateral triangle, the conversion between angular and linear geometry.

29.53059 (the lunation) converts those geometries into temporal measure, counting the Moon’s monthly cycle.

223 / 235 encodes the Saros-Metonic ratio, the long-term reconciliation of solar and lunar years used to predict eclipses.

254, the number of sidereal months in a 19-year Metonic cycle, translates these cycles back into linear distance.

Hence, the factor 2π / (3√3), the same one that yields the Sarsen diameter, is simultaneously the ratio linking circular and triangular geometry and the ratio that unites the solar, lunar, and draconic years when expressed in days.

The same bridge is expressed through another form of the Sarsen constant:

1 000 000 / (28×29.53059) = 1209.4

Here 28 (the four-week lunar month) combines with 29.53059 (the synodic month) to produce the same 1209 inches. In this way, 28 acts as the temporal counterpart to the geometric bridge 2π / (3√3).

This synthesis unites four domains of measure:

Geometric: the circle and triangle (π, √3);

Solar: the year (365.25);

Lunar: the month (29.53) and long cycles (223, 235, 254);

Planetary: the synodic periods of the visible planets.

At their intersection lies the 1209-inch constant, the Sarsen modulus, numerically linking Stonehenge’s design to the same harmonic structure found at Giza. It appears to mark the ancient reconciliation of time and form: where counting became geometry, and geometry became a language for the heavens. The Sarsen Circle diameter links up to the cycles of the planets, the sun, the moon, and precession.

The Y-Holes

Among all the concentric features of Stonehenge, the Y-holes occupy a special position, numerically, geometrically, and symbolically. Using the data in the table, the diameter of the Y-hole circle is 2 109 inches. This figure is remarkably close to 10 x 365.242 / √3 = 2108.727, that is, ten solar years in days divided by √3, the constant that relates the side of an equilateral triangle to its height. In other words, the Y-holes define a circle whose diameter can be read as the product of a temporal constant (the solar year in days) and a geometric constant (√3), scaled by a simple integer, ten. The correspondence is exact to within less than a third of an inch. A similar operation, applied to the bank diameter, gives 18 x 365.25/ √3 = 3795.789 inches. Finally, the Y-holes and bluestone circle (24.25 m) differ by a factor close to 7π / 10 ≈ 2.199, again uniting a circular constant (π) with a simple integer ratio.These cross-ratios weave the monument into a network of proportional correspondences whose governing terms are the very constants, π, √3, √5, and φ, that appear at Giza and throughout ancient canonical geometry.

The purpose of this article is to interpret the data presented in Chamberlain and Parker Pearson's paper, but measurements and interpretations of Stonehenge vary and there is plenty of scope for that. For example, in Martin Doutré's excellent analysis, a different diameter is used for the Y holes, 178 ft instead of 176 ft. He has interpreted them as a φ-reduction of the 288-ft Aubrey Circle and as a metrological “calibration” linked to the Menkaure Pyramid’s base and to the 1728-series numbers (17.28, 207.36, etc.) used in geodetic reckoning, all of which is absolutely sound. With the figures in the Chamberlain and Parker Pearson paper, the Y-holes can encode a circle whose diameter equals ten solar years scaled by √3, binding time, geometry, and proportion in a single gesture. The adjacent Z-holes, with their precessional ratio of 72, complete this relationship. Either way, the Y and Z circles form the metrological heart of Stonehenge’s inner design: a compact expression of the same integrated cosmology that also may have animated the measures of Giza, time being translated into geometry.

The Solar and Venusian Ratios

When the diameters of the Stonehenge circles are expressed in inches and divided by 365.25, then multiplied by 8, a striking regularity appears. The counterscarp bank and the Aubrey Holes, in particular, produce values of 100.03 and 75.06, respectively, owing to a perfect 3:4 ratio between them. This is significant on several levels. Numerically, 3:4 is the harmonic interval of a perfect fourth, one of the three foundational consonances of ancient tuning systems (with 2:3 and 4:5). Geometrically, it defines the ratio between the sides of a Pythagorean right triangle (3–4–5), a form intimately connected with ancient temple and pyramid design. Astronomically, the scaling by 8 recalls the octaëteris, the eight-year Venus–Earth cycle that aligns solar and lunar calendars every 99 lunar months. So, this single column of data binds together solar time (365.25 days), Venusian recurrence (8 years), and harmonic proportion (3:4), all in the measures of Stonehenge’s outer and inner rings.

When the diameters given by Parker Pearson are converted to inches, a simple and elegant proportional system emerges. They reveal a set of rational harmonic ratios between each ring. such as 100 and 75, seen here in the counterscarp bank and the Aubrey holes. To explore whether these relations might tie to cosmological time, the diameters were also divided by the constant:

κ=1/ (6×√3×365.25) (or it could also be expressed as 1/ (6×√3×365.242199)

This constant intertwines three ancient frameworks:

365.25 or 365.242199, the solar year in days;

√3, the geometry of the equilateral triangle and hexagon, linking the circle to the year’s sixfold division;

6, the hexagonal and sexagesimal symmetry underlying both geometry and the early calendars (the Babylonian 6-, 60-, and 600-year reconciliations of lunar and solar time).

When each ring’s diameter (in inches) is expressed as a multiple of κ, a clear progression appears:

Structural component | Diameter / κ | Approx. value |

Counterscarp bank | 1.203 | ≈ 6 : 5 |

Ditch | 1.102 | ≈ 11 : 10 |

Bank | 1.002 | ≈ 1 : 1 |

Aubrey holes | 0.903 | ≈ 9 : 10 |

Y holes | 0.556 | ≈ 5 : 9 |

Z holes | 0.400 | ≈ 2 : 5 |

Sarsen circle | 0.318 | ≈ 1 : π (0.3183) |

Bluestone circle | 0.252 | ≈ 1 : 4 |

Conclusion

The analysis presented here has deliberately confined itself to a limited set of dimensions, those published by Chamberlain and Parker Pearson, in order to test how much can be extracted from a cautious and widely cited modern dataset. Even within these constraints, the results are striking. When the principal diameters of Stonehenge are examined proportionally and expressed in inches, a coherent geometric structure begins to emerge, one in which circles, triangles, and simple ratios link the monument’s elements together in a manner that appears systematic rather than incidental. Constants such as π and √3 recur with notable regularity, and several of the diameters resolve cleanly when interpreted through lunar and solar numbers. The Sarsen circle, in particular, appears to function as a geometric key, capable of generating other dimensions through simple transformations, and of anchoring relationships that resonate with both astronomy and geometry.

At the same time, it must be emphasised that the figures used here represent only one possible set of measurements. Stonehenge has been surveyed repeatedly over the last three centuries, often with different aims and different reference points. As Harry Sivertsen has noted, early investigators such as Stukeley, Petrie, Atkinson, Thom, and Michell each defined the Sarsen circle slightly differently, whether by stone centres, lintel edges, or inner and outer faces. Petrie’s 1880 survey, for example, placed the inner diameter of the Sarsen circle at 97.325 feet, a value remarkably close to 100 Roman feet, and arguably closer to a true design intention than later averages. Sivertsen’s discussion of lintel widths and their relation to lunar counts further underlines how sensitive astronomical interpretations can be to seemingly minor differences in definition. The fact that different surveys yield different but closely related values does not weaken the case for intentional design, but rather suggests that the monument operated within tolerances that allowed symbolic and astronomical relationships to be expressed without requiring modern notions of precision.

It is also clear that the dimensions explored here represent only a fraction of the available evidence. Stonehenge is not merely a set of concentric circles but a complex ensemble of rings, post-holes, stones, avenues, and sightlines, many of which involve specific counts as well as distances. The number of stones, lintels, and pits is as significant as their spacing, and any interpretation that neglects counting risks missing the monument’s calendrical and computational character. In this respect, Stonehenge increasingly resembles an analogue device, a physical system in which time, number, and geometry are made visible and walkable. The Aubrey holes, the Z and Y holes, and the relationship between inner and outer rings all point toward an integrated scheme in which measurement and counting worked together.

Finally, the comparison with Giza, tentative though it must remain, is suggestive rather than definitive. The appearance of closely related geometric constructions, particularly those involving circles, equilateral triangles, and the interplay of π and √3, raises the possibility that Stonehenge participates in a much broader tradition of astro-geometric thinking. Whether this reflects direct transmission, convergent development, or a shared response to the same astronomical realities is an open question. What can be said is that the data do not support the view that Stonehenge’s geometry arose by accident, intuition alone, or unsystematic pacing. On the contrary, even a restricted reading of the measurements points toward deliberate planning informed by geometry, astronomy, and a sophisticated understanding of number.

This article has therefore offered only a small glimpse into what Stonehenge may encode. A fuller study would need to incorporate alternative surveys, a wider range of structural elements, and a more explicit integration of counts, alignments, and calendrical cycles. Nonetheless, the evidence examined here is sufficient to challenge the prevailing assumption that prehistoric builders lacked mathematical intelligence. Stonehenge emerges instead as a monument conceived within a coherent metrological and astronomical framework, one that deserves to be studied not only as archaeology, but as science expressed in stone.

Bibliography

Chamberlain, Andrew & Parker Pearson, Mike, 2007, Units of measurement in Late Neolithic southern Britain, From Stonehenge to the Baltic. Living with Cultural Diversity in the Third Millennium BC (pp.169-174), Base Unit (‘foot’) and Conversion Ratios

Doutré, Martin, Stonehenge pt 1

Sivertsen, Harry, 2020, The Metrology of Stonehenge, (63) The Metrology of Stonehenge 2020

Comments